By Dave Parsons

Once upon a time, some 35 years or so ago, there was a songwriter in Nashville, Tennessee named Kent Blazy. In the late 1980’s he was introduced to a then unknown demo singer/songwriter. The aspiring artists brought the idea, and as the story goes, Blazy delivered the first verse within 15 seconds and the collaboration became If Tomorrow Never Comes. It was the first number one song Blazy had written and the first number one written and sung by that demo singer who is named Garth Brooks. That story is like a fairy tale, but Blazy’s story began long before that.

Kent Blazy grew up in Lexington, Kentucky, playing in various local bands. In the 1970s, he was a guitar player for Canadian legend Ian Tyson. After winning a national songwriting competition, Kent moved to Nashville. In 1982, Gary Morris had a hit with Kent’s song Headed For A Heartache. Other cuts followed with The Forester Sisters, T. Graham Brown, Donna Fargo and Moe Bandy. In addition to If Tomorrow Never Comes, Blazy and Brooks collaborated on four additional Top 5 songs with Ain’t Goin’ Down (’Til The Sun Comes Up), Somewhere Other Than The Night, It’s Midnight Cinderella and She’s Gonna Make It. Kent also was a co-writer on the Brooks & George Jones duet Beer Run as well as on That’s What I Get For Lovin’ You by Diamond Rio and Gettin’ You Home (The Black Dress Song) by Chris Young.

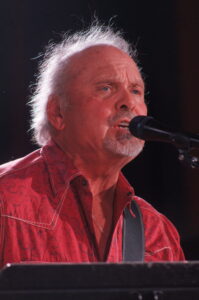

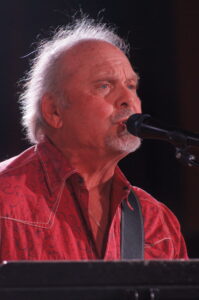

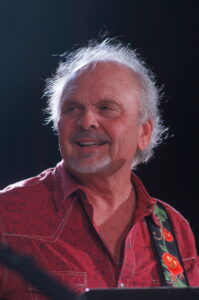

As an entertainer in his own right, Blazy has 8 or CD’s to his credit, the most recent being From The Beatles To The Bluebird. In March of 2024, Blazy was preparing to do a concert with his band at The Listening Room in downtown Nashville. He was gracious enough to take a few minutes out of the pre-show preparations to sit down with me and discuss his career.

First of all, the latest album is great. I got to listen to it on the plane coming down today. Explain to me a little bit about how all that came about with the Beatles and the whole thing.

“Yeah, it was a lot of fun. You know, I was over in Liverpool and they have the statue of the Beatles on the dock there. And I had my picture taken with it and I was wearing a Bluebird (Café) sweatshirt because I’d done a benefit for them a couple weeks ago and they gave it to me. It was cold in June, so I saw the picture of me with the Beatles and the Bluebird Cafe and I thought, that’s a great album title. Now I’ve got to do write these songs to go with it. I mean, if it hadn’t been for the Bluebird, Garth would have never got a record deal.”

So, were the Beatles a big influence when you were a kid?

“Well, you know, they were a big influence to me on how they changed the world. I wasn’t the kid that started playing guitar because of the Beatles. For me, it was Roger McGuinn of the Byrds. I heard his 12-string, and then that made me want to play guitar. But the Beatles have always been such a big influence to me on how they’ve done everything.

They changed the world as far as I’m concerned. They changed politics, they changed religion, they changed music, fashion, just about everything. And it’s still going on. McCartney’s still out there playing and Ringo’s still out there playing. God bless him.”

That’s what I was thinking coming down here, could you hear McCartney doing If Tomorrow Never Comes?

“Actually, an English -Irish guy by the name of Ronan Keating cut If Tomorrow Never Comes kind of in a different way. And it was a worldwide hit except everywhere in America. It was more of a pop thing, and I’ve had a lot of different cuts, and I could see McCartney taking it and turn it into something else.

And the other cool thing is a couple of guys that are big managers here in town heard the record, and they pitched February 9th, 1964 to Apple to see if they wanted to use that as a theme for when the 60th anniversary was.

I thought, hey, that’s cool, these guys think enough about it to send it to the big lucky mucks at Apple. And the other one was, you know, I could see McCartney doing I Wanna Die Young at a very old age, because he was the influence for that, you know. He’s 84 and he’s still out there playing it in the same keys he sang with in the Beatles, which I hate him. (laughs) He is playing three hours a night, at 84.”

The song on the CD about the birds on the wire.

“That was written for Kim Williams. Okay. I don’t know if you know Kim’s whole story or whatever. He was a chemical engineer and was in a room that exploded. And he had burned over 90 percent of his body and he had like he was in the hospital for a year, had a hundred operations and he decided that God wanted him to be a songwriter.

So he moved to town and I’ve never seen anybody work as hard as he worked. He wrote seven days a week, four times a day and he was such a fun guy, and a hard worker. You know he’s an inspiration to anybody else who goes oh I only write from noon to three or something. In 4 or 5 years he was songwriter of the year at ASCAP.

So it just shows you what you can do. Garth introduced me to him because Kim hated one of the lines in a song that Garth and I were working on. Garth called me up and said “hey this guy I played him one of our songs and he hated it. You want to write with him?”

I’m like what? Why do I write with somebody that hates my songs? He said well he liked one line and he thought he could turn it into a title. So I said well sure and Garth then told me that Kim had been burned over 90 percent of his body.

So, of course, Garth was usually late and Kim was usually early and I opened up the front door and I was pretty much in shock looking at this guy. But, you know in about 10 minutes you forgot about it, because he was just such an amazing human being but we got together that first day and we were working on the song that he hated but liked the idea from. We ended up writing another song that Garth ended up cutting and when we got it done Garth said “this is gonna be on my third album and I thought you don’t even have a record deal yet.” So it came to third album, you know, and there it was on the album….it’s called Cold Shoulder.

And so I was down in Texas doing some shows this last year, and down there they have a lot of birds on highlines. I had just been to Ireland to hear Garth, and he came over and sang it right next to me, and I’m like, are you trying to tear me up or what?

I was just down there and this whole song started coming to me about Kim, you know, and I sent it to him, he said, I can’t listen to it, I don’t even want to know he’s gone. I said ok but I just thought you might want to hear it. I’ve gotten a lot of good feedback from people that knew Kim, and that makes me feel good, because he was such an amazing being.”

The process of writing with other people, from other songwriters I’ve interviewed, it’s either love it or hate it. Is that how it is for you?

“Well, for me now, it’s pretty much, it’s got to be people I love. And you know, when you’re with publishing companies or whatever, they are setting you up with people who don’t know who you are and you don’t know who they are.

And sometimes it clicks, and sometimes it doesn’t, I always equate it to a first date. You never know how it’s going to go. But you know, you just get with a lot of people that it just doesn’t click, and they may be the best writer in the world, but it’s just you two, the chemistry is not right. You know, but from the minute Garth and Kim and I were together, the chemistry was just right there.

I know the story about If Tomorrow Never Comes, and you mentioned the Bluebird earlier and how all of that connected.

Yeah, we had written that song, and it’s funny, we wrote that song in this little house I was in that was like a block from the Bluebird. And we thought we’d written a good song, and we pitched it around town for a year, and him for a year, and nobody was interested. They said nobody’s going to sign somebody named Garth, you know.

And so he got to play one night at the Bluebird, they called him up and said, hey, this artist was supposed to do a showcase, he didn’t show up, will you come sing one song. He came in and he sang If Tomorrow Never Comes, and somebody from Capitol was in the audience to hear the other guy, but he came up to Garth afterwards and said, hey, you know, maybe we missed something, why don’t you come back in, and he went back in and got a record deal because of that song, and it ended up being his second single and first number one.

So if it hadn’t been for the Bluebird, who knows if there’d be a Garth Brooks.

I’ve got to ask you Ain’t Going Down ‘til The Sun Comes Up. There’s a lot of words in that.

Well Garth called me up and he said I want to write a song with machine gun lyrics. So we called Kim and we got together. I had just moved into this house and we went out on the back deck and just wrote machine gun lyrics and laughed all day. He had kind of a story he wanted to tell and we usually just do guitar vocals with work tapes and Garth said, I want a drum machine on this.

Drum machines back then were really bad. And at the guitar player’s program in a drum machine, it’s really, really bad. So I had this little drum machine thing going, and Garth and Kim were standing behind me, and, I remember it as just a day of laughing and having fun, and that was usually how it was with Kim and Garth. But we wanted to write something that had machine gun lyrics, as Garth put it.

I guess machine gun lyrics just kept turning them out and turning them out. And trying to get them the fall right, that was the hardest part. We started the last verse, and we were just stumbling and stumbling for about an hour, and finally Kim said, everything has to end with I -N -G, so it flows good.

How did you end up being a songwriter?

Well, you know, the main thing is, this is kind of crazy, but I grew up as a little kid in Woodstock, New York. And Woodstock, before the festival, was still an artist community. The Hudson Valley painters were from there. We had as a little kid I’d meet people that were authors that would sign a book to me or you go over and see somebody and they’re finishing painting and it’s as big as this wall and I thought well that’s a good way to make a living.

And we moved to Kentucky which was kind of the wasteland of creativity at the time and so we would we were the we were the northern hillbillies. We would go home every holiday and stuff like that so I was always in touch with Woodstock and it had that whole creative scene going on and then Dylan moved there about the time I started playing guitar and when he had his motorcycle accident my cousin was the first policeman on the scene so you’ve got that kind of thing going on but it just that creative thing made me want to be an artist the painter at first and so I was studying that.

When I was a little kid, and my sister was way better than me. So I said, OK, you do that. I’m going to start writing poetry. So I started writing poetry, and I got some things in high school magazines and yearbooks. I thought, well, somebody must like it enough to publish it. And so the minute I got a guitar, I thought, I’m just going to start writing songs and put whatever I write, poetry -wise, to music. And that kind of where I went from there.

So I didn’t know of anybody else’s songs. So might as well learn some of my own. And then I finally started learning other people’s. But I studied Dylan immensely, like everybody. And all those 60s people were writing such great songs that it made it easy to follow a path of where I needed to be going. And then I didn’t get in the country because of country. I got in the country because of the country guitar players that were so good. I kept hearing these guys that were so phenomenal. And then the Byrds, who were my favorite, kind of went into country music for a little bit and did Sweethearts of the Rodeo.

So everything was kind of pushing me that way. And I had some people that were interested in songs in LA, but some people that were interested in Nashville. And I thought, well, Nashville is a whole lot closer. I can drive home if I need to with my tail between my legs. So, I ended up moving to Nashville and just kind of dug in. And when you get here, you kind of have to do an every irons in the fire kind of thing.

I had a three -night -a -week gig and a smoky bar. And I was writing songs during the day. I was doing sessions playing guitar for people. And then I started my own studio. Songwriting up till about the time of Garth really didn’t pay much better than it pays right now. There wasn’t anybody really selling millions of records or anything like that. You’d have a cut on somebody like the Forrester sisters, and it might sell 70,000 copies.

Soundscan wasn’t necessarily being fair at the time. They didn’t get things right until they went to all computers instead of calling the record stores. Then, suddenly he started showing up on the soundscan, and then other country acts did too.

Yeah, there was a music store up by where I lived that the girl was one of the reporters, the recording stores, and she said they never got it right. She said every time we’d have this big selling album over here, and they had it down at the bottom.

I guess it was basically until that came along about, what, 91, 92 that it started. It was kind of a favoritism thing. Whatever the people in the store listened to and liked, oh yeah, they’re selling the best.

Do you think somebody could do that now, which you did, because as expensive as Nashville is and the way the industry’s changed?

I think the industry’s changed so much. It’s almost like you have to come to town and pretty much be an artist for somebody to sign you to a publishing deal to write songs. Even then, they still don’t pay draws really because we used to get paid by mechanicals and when they stopped making CDs all the mechanicals quit coming in.

I’m just going to ask you, as far as the album goes, do you have any hopes for making it just to make it, or to try to get some airplay…

Well, you know, I love playing it live, as you’re going to hear tonight. We’re going to do some songs. And these guys are the guys who actually played on the record. We’re going in and cutting another record in two weeks. So these songs just came out in November.

You cut this album in like one day?

Yeah, one day. I did it myself. We cut all the basic tracks and vocals. I usually play and sing at the same time. And then overdub like guitars or harmonies the next day.

And we cut it at Sound Emporium, which has a great room. We are going back there because they all love that room, and do the same thing. The thing that we do that helps is I get with them and we run over all the songs sometime the week before.

So everybody charts them all out. Everybody knows them. And it makes it a lot easier to get 10 songs done in one day. Why doesn’t everybody else do that? You would think that would be the way to pay for everything so they can take their time.

So you’re doing a whole other record. Tell me a little bit about it and then we’ll get out of here and let you get ready for the show.

“It was kind of inspired by listening to Jason Isbell. He’s so good at telling stories about people from his past. And last year I had two people die that were real important to me in my 20s that I kind of lose track with. One was a girlfriend and one was this guy I played in the band with and they both passed away.

I kind of wrote songs to honor both of them. And then it kind of turned into this whole other thing about writing some songs about the music business. And rolling up in Kentucky was like the bubble of the Bible felt like Nashville and I had a preacher telling me, you can’t play the devil’s music and all that.

I kind of wrote a song for him. And so it kind of was looking back on parts of my life that I hadn’t really looked at in a long time. Coming up with some songs that would mean something to somebody who heard them who knew where that was coming from and it means something to me. A lot of it was autobiographical, other pieces in there and stuff. I mean, they don’t want to write what I want to write here in Nashville anymore.

I just write what means something to me and it’s very fulfilling. Because you’re an artist and a writer too rather than just writing the formula to get radio. And you know, it seems like people appreciate it. So that’s good. If they were throwing tomatoes, I’d quit. And my favorite thing is to play electric guitar with a band. So, I get to do that.

And about 20 minutes later, Kent Blazy took the stage with his band and walked the audience through his songwriting, and recording career. He punctuated the hits with stories of how they came to be, and set up the process of writing the songs from his own CD releases. The crowd went along for the journey in a room set up to listen to the music and to the storyteller who created it.

Kent Blazy Setlist:

1 February 9, 1964

2 If Tomorrow Never Comes

3 From The Beatles to the Bluebird Cafe

4 Writing Songs

5 Why Ain’t I Running?

6 Following The Footsteps of Dylan

7 If it Wasn’t For the Byrds

8 Goodbye Tom Petty

9 I Wanna Die Young

10 That Would Be Me, Without You

11 Thanks To You

12 All I Can Think About Is Getting You Home (Black Dress Song)

13 Ain’t Going Down Until The Sun Comes Up